U.S. income tax rules and their impact on Canadians moving to the United States

Questions and Answers from an interview with Kerry Gray, partner in the Global Employment Solutions Network Group, Ernst Young Canada LLP

Q: One of the first questions that I would like to ask you about is the tax implication of moving away from Canada — of changing one’s residency status.

A: Under Canadian law, unlike U.S. law, we tax individuals based on residency. The U.S. income tax is based on residency and citizenship

Once a person leaves Canada, he or she is no longer taxable in Canada on non-Canadian income. There are still types of income generated in Canada that they are paying tax on, but in general they are longer subject to worldwide taxation in Canada. What Canada also does is deem individuals to have disposed of certain assets on the date of departure from Canada. Any appreciation that they have on those assets while they were residing in Canada will be subject to a tax. Departure tax is nothing different, it is just income tax that is levied at the time ones ceases to be a resident or departs from Canada.

Q: Do you crystallize everything when you leave Canada?

A: Generally, yes, you are deemed to have sold everything from a Canadian perspective the day that you cease to be a resident.

And all the normal tax rates and exemptions apply?

- Answer. That’s correct. A couple of things that deemed disposition does not apply to includes assets like RRSPs because as a non-resident when you take money out of an RRSP, you still pay Canadian tax. It is not at the old regulated graduated rates and you don’t have to file a return, but Canada would still have the right to tax it. Deemed disposition would also not apply to real property in Canada.

Not until you actually sold the property?

- Answer. Correct, because when you actually sell real estate later on you would still be taxed in Canada

So deemed disposition primarily applies to what we’d refer to as a non-registered investment portfolio?

- Answer. Yes, most commonly to publicly traded stocks in a portfolio.

What else?

- Answer. The deemed disposition rules also apply to personal-use property such as a car or boat, things like coins, paintings and jewellery — if the fair market value of each item or set is greater than $1,000 — foreign real estate and securities, bonds and other commercial paper, unlisted shares, and your interest in a segregated life insurance policy.

Do you have to ante up your departure tax in cold hard cash?

- Answer. For small amounts of departure tax — under $50,000 in taxable capital gains — you don’t actually have to pay. If you sold the asset when you left you have to pay your tax. If you don’t sell it and you have your departure tax apply, you are supposed to post security with the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency.

What kind of security?

- Answer CCRA normally favours letters of credit, bank guarantees, mortgages, negotiable stocks or bonds. When security is posted, the tax will be payable when the property is actually sold and taxpayers aren’t charged interest between the date of departure and the date of disposition.

Now since you’ve had to crystallize your gains, does this affect your adjusted cost base of the investments you may still be holding?

- Answer. No, and that is where if you are moving to the U.S. you need to talk to a tax professional. On the U.S. side of the border, you are not deemed to have bought for the crystallized value on the day that you moved.

Ouch! You mean you are deemed to have bought it the day that you actually acquired the security?

- Answer That’s right.

So you are going to have two sets of capital gains?

- Answer. That’s correct. If someone’s moves into Canada, Canada deems you to buy things the day that you move in and sell things the day that you move out. The U.S. does not do that. Canada says, “Okay, we have some transitional rules because there is an exposure to double tax, in that the U.S. doesn’t say that your basis is the fair value the day that you move into U.S.” So there are some transitional provisions in place in Canada allow you to claim a foreign tax credit against the Canadian tax so you are not double taxed.

So since the U.S. doesn’t recognize the basis bump when you sell, if you have to pay U.S. tax, Canada will give you a credit for the amount of U.S. tax that you owe on the gain up to the point in time that you left Canada?

- Answer Correct. So let’s say your deemed disposition is $100,000 when you left Canada, but it grows another $50,000. You can’t claim U.S. tax on a $150,000 against your Canadian tax on a $100,000. You can only pick up the U.S. tax on the $100,000.

So are there circumstances where it just makes sense to sell the investment to avoid all this complicated stuff?

- Answer. Depending on what the asset is and what you think is going to happen with the asset and what state you are moving to you might want to actually sell the asset and rebuy it instead of just having the deemed disposition. This is where it the planning becomes interesting. The individual states in the U.S. have various tax rules. Some have no personal tax, some have personal tax, some don’t tax capital gains. So you have to understand where you are going, and know the beast you are looking at.

So it is not enough to say that I am moving to the U.S., you have to say I am moving to such-and-such a state. I don’t think that Canadians have that appreciation because while we have different tax rates provincially, barring Quebec, most of our tax rules are homogeneous. I don’t think Canadians have an appreciation for the independence that U.S. states have.

Anything else?

- Answer. Can we go back for a moment on the real estate — to your Canadian home?

- Generally you never pay tax on the gain on your principal residence in Canada. And that holds true in general so long as you sell your home it the year that you leave or by the end of the calendar year following the year of departure. In the U.S., however, there is a special provision on the Canada/U.S. income tax treaty that does give you a basis adjustment up on that home. So even if you close on your home sale after you arrived in the U.S., generally you won’t pay U.S. tax as long as you sell it for an amount of no greater than the value at the point of time that you left Canada.

- So it is a special provision under the treaty that allows you to revalue your home. But once again, you have to check and see if the individual state [to which you’re moving] follows the treaty. It is not a slam-dunk that individual states do that.

So you can’t assume anything?

- Answer. That’s right. You have to check out everything.

Tax Haven Banking

There’s no place to hide

Offshore banking isn’t illegal, but keeping it secret from the taxman is

Jonathan Chevreau – Financial Post 05-May-2002

You could leave a trail for the taxman when you try to access your money in an offshore tax haven, like the Caymans. One of the fantasies overtaxed middle-class Canadians occasionally indulge in is of setting up a secret “offshore” bank account located far from the grasping arms of the taxman.

Fuelled by books like Alex Doulis’s Take the Money and Run! and a glut of imitators with the words “tax haven” in their titles, the notion seems to be based on the perception the average Joe should be able to get away with what he thinks the rich are doing.

To be sure, anyone can open an “offshore” account with a foreign bank. You can do that on vacation in the Bahamas merely by walking into any bank, including the big Canadian branches operating in the Caribbean.

“It’s perfectly legal to open up an offshore bank account,” says Tom Boleantu, president of Calgary-based Expatriate Group Inc.” but you have to file taxes on worldwide income as a Canadian resident.”

The group’s Web site www.expat.ca provides information on setting up offshore accounts but also clarifies that it “does not assist nor condone tax evasion or money laundering.”

Evidently part of the fantasy of the offshore bank account is the mistaken belief you can conveniently “forget” to report any interest or capital gains generated by the offshore account, and that the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency will be none the wiser. If you believe the offshore havens will veil your activities under the cloak of secrecy they once were reputed to have, you’re likely to be nabbed for tax evasion.

We are now in a world of globalization and technology, and use of credit and debit cards leaves an audit trail clear enough for any determined tax collector to put two and two together. Over the past year, most of the popular tax havens have begun to cave in to the disclosure demands of tax-hungry Western democracies.

David Lesperance, legal counsel to Hamilton, Ont.-based Global Relocation Consultants S.A., refers to offshore bank accounts and international business corporations as merely the bricks to build an audit-proof tax structure. “Without a properly designed house, they’re useless. You’ll pay just as much tax on your bank account with Barclays in the Caymans as with a Royal Bank account around the corner.”

In February, the United Kingdom said it will report non-resident tax accounts to countries with which it has a tax treaty. That includes Canada, Mr. Lesperance says.

The pressure on traditional tax havens to, in effect, renege on earlier “privacy” obligations to offshore clients is coming from two international initiatives: the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Financial Action Task Force. Much of this, Mr. Lesperance says, was set up under the guise of eradicating money laundering by drug smugglers. Most big-name reputable financial institutions are complying. When it comes to choosing between “protecting” a small individual holder of a bank account and paying a $50,000-a-day fine, which would you choose?

If you still wish to pursue the fantasy, that may leave the Fly by Night Bank of Lower Slobovia or some similarly fictitious scam artists. In which case, your problems may soon be worse than paying tax on interest: You could end up losing your entire principal.

Even if you could find a rock-solid foreign bank that looked the other way when the tax authorities came calling, there remains the problem of how to access the money. Suppose you were “successful” in diverting under-the-table cash deals to an offshore bank account that now generates undeclared income. What do you do when you want access to those funds? If you’ve been issued a major credit card, you may be out of luck again. Mr. Lesperance says the Internal Revenue Service in the U.S., Inland Revenue in the U.K. and the CCRA have won a court order to get access to all MasterCard and American Express accounts in the Caymans, Bahamas and British Virgin Islands. The next thing you know the taxman is knocking on your door, wondering how you were able to afford a $10,000 spending spree on your new Barclays Visa card.

Once upon a time it may not have been cost-efficient for governments to go after the little guy, but now it is, Mr. Lesperance says. The Web site (www.quatloos. com/newsltr) describes how offshore banks used to offer “secret” accounts for U.S. citizens, which were believed to be effective in hiding money from the IRS. They offered offshore credit or debit cards that let U.S. citizens access the account from anywhere in the world, and use the cards to purchase goods without leaving a record. But today, the site says, “offshore credit cards have suddenly become a huge tax trap that will send literally thousands of U.S. citizens to jail for tax evasion, and will net tens of billions in back taxes, penalties and interest to Uncle Sam.”

It used to be that the big banks in the Caribbean — including Royal Bank of Canada — were doing nothing wrong under the laws of the countries in which they operated. They were not required to co-operate with tax authorities or to inform them whose accounts offshore credit cards were linked to.

But the laws changed last summer, when the OECD and the FATF released their blacklists of offshore tax havens. These nations were warned that if they did not co-operate with tax authorities in the U.S. and Europe, they would suffer severe retaliatory measures, including trade embargoes. The IRS then imposed requirements that required U.S. banks to file a Suspicious Activity Report whenever money was transferred to one of the tax havens on the blacklists.

With all those tourism dollars at stake, the Bahamas, Caymans and Antigua quickly capitulated.

The heightened risks of going offshore were outlined last June at the Ontario Securities Commission’s Web site (www.osc.gov. on.ca). Its Investor Alert section notes that offshore jurisdictions with lower levels of regulation and securities laws mean less protection for investors.

Which doesn’t mean the average tax-weary Canadian can do nothing. If you have a lot of active non-Canadian source business income or have an electronic business selling services around the world, there may be bona fide corporate structures and offshore trusts that may lighten the load in a way that’s still acceptable to tax authorities.

Alternatively, you could “take the money and run,” by permanently leaving the country — selling your home here, severing all other ties to Canada, collapsing your registered retirement savings plan and paying a withholding tax of 15% to 25%. But that’s another article.

Warning Notice: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada Bureau du surintendant des institutions financières Canad

Professionals Planning to Work Abroad (or coming home) – March 3rd 2016

APEGGA Professional Speaker Series

On March 3rd The Expatriate Group did a presentation for APEGGA. The topic was “Canadians planning to work abroad (or come home)”. Living as an Expat Canadian is much more than tax implications. During the presentation we identified the 6 dimensions of Expat Planning: Goals, Tax, Lifestyle, Wills, Currency/Banking and Financial Planning. This presentation gave us the opportunity to have open dialogue and walk the attendees through what each dimension looked like as a non-resident. Some of the highlights we discussed were non-residency, culture shock and wealth and strategies for saving.

Non-Residency: Individuals looking to eliminate their tax obligation to the Canadian Government on world-wide income do so by…. Unfortunately, the answer is not so simple. In Canada, non-residency is not a straightforward test as some people might think. Each situation is unique and a case by case basis. We have individuals contacting us daily trying to find out what is required and not required as a non-resident. CRA looks at the total picture – investments, banking, tax, social benefits, and social ties. There are minor ties and major ties to both Canada and in the new country of residence that are used to evaluate tax residency status and obligations.

Culture Shock: Personal disorientation (culture shock) occurs when a person is experiencing an unfamiliar way of life different from their own. Successful adaptation to new a new cultural environment is an important part of the expat transition. There are so many differences when going to a new country: different times to eat, the direction of traffic, food, cultural norms for small talk (what to ask/not ask). Once the change has been identified the individual must come up with coping strategies to adapt. The faster you adapt the faster you are able to overcome culture shock. We find that reverse-culture shock when returning to Canada is much more difficult to overcome and requires much more preparation and concrete readjustment strategies in order to have a successful repatriation to Canada.

Wealth is Complex: Going abroad has many concerns. Most people take care of the urgent pieces of work (i.e. tax, house rental, etc.) however there are many considerations. Banking, currency exchange, pensions, cash, savings, investment accounts, corporate structure, company headquarters, spousal departure, property, capital gains,  worldwide income, non-resident reporting requirements, tax treaties, Part XII, S216, capital cost allowance, rental expenses, international estate planning, return to Canada, immigration regulations, working visas, world-wide income, employment contracts, health care, repatriation of savings – the list is extensive. The more wealth one has, the more complex the picture gets. It is important to have a professional comprehensive review of these wealth issues – in fact there are tax implications on many of them.

worldwide income, non-resident reporting requirements, tax treaties, Part XII, S216, capital cost allowance, rental expenses, international estate planning, return to Canada, immigration regulations, working visas, world-wide income, employment contracts, health care, repatriation of savings – the list is extensive. The more wealth one has, the more complex the picture gets. It is important to have a professional comprehensive review of these wealth issues – in fact there are tax implications on many of them.

Strategies for Saving: Keep in mind that if you are working overseas you should take advantage of the tax free situation by saving additional income that you might earn. We recommend that our clients keep track of their personal financial accounting prior to departure, while they are away and upon return to Canada. It is common for Expatriate Canadians to hold assets in many different jurisdictions. We recommend consolidating your accounts  under one Canadian advisor and saving 1/3 of your salary while overseas in Canadian held investment accounts. We recommend this strategy for Estate planning purposes, your Canadian will covers your assets in Canada. Cash flow planning for retirement years should begin as early as possible – especially when the income tax liability in Canada has been reduced. Non-resident withholding taxes are applied to: dividends, rental payments, pension payments, OAS, CPP, RRSP payments, RRIF payments and annuity payments. However, capital gains may be tax-free for non-residents. Canada maintains international tax treaties with many different countries and the amount of withholding tax applied to non-resident income is based on a case-by-case basis.

under one Canadian advisor and saving 1/3 of your salary while overseas in Canadian held investment accounts. We recommend this strategy for Estate planning purposes, your Canadian will covers your assets in Canada. Cash flow planning for retirement years should begin as early as possible – especially when the income tax liability in Canada has been reduced. Non-resident withholding taxes are applied to: dividends, rental payments, pension payments, OAS, CPP, RRSP payments, RRIF payments and annuity payments. However, capital gains may be tax-free for non-residents. Canada maintains international tax treaties with many different countries and the amount of withholding tax applied to non-resident income is based on a case-by-case basis.

What you should do today: The first step to successful expatriate work abroad professional is to write down some clear goals (both personal and financial). Spend as much time as possible planning and documenting your expatriation from Canada to ensure a clear roadmap for years ahead. You will be amazed by the growth of your net worth while overseas when sticking to a well thought out financial plan. Pick one dimension of the wealth map (Goals, Tax, Lifestyle, Wills, Currency/Banking and Financial Planning) and dedicate some time to it today. A few hours will pay off forever! We have many clients that are expatriating, repatriating, retired and just starting out with their careers and they all have two things in common: they have a plan and they follow a comprehensive approach to their wealth. Please contact our firm for a consultation if you are interested in a review of your non-residency questions and concerns.

About the Author: Jeanette Boleantu is a non-resident wealth strategist with The Expatriate Group. Her mission is to not only create better planning but also to implement those strategies. This approach gives clients peace-of-mind and helps them to meet both their personal and financial goals.

6 must-know tax facts for Canadians earning abroad – Repost

By Mark Gollom, CBC News Posted: Apr 25, 2012

The Canada Revenue Agency defines someone as a “factual resident” for taxation purposes if they maintain “significant residential ties” to Canada.

Canadians can travel far and wide, but never quite far enough to avoid paying taxes. Whether you’re working in a bar in Paris, or on a global trek, you may still be on the hook for paying tax on income earned.

Here are some things to keep in mind to make sure you don’t run afoul of the Canada Revenue Agency on your return to Canada if you’ve earned money in another country:

1. Canada can tax you based on money earned here and abroad

“Residents of Canada have to pay tax on their worldwide income to Canada no matter where they earn it,” says Georgina Tollstam, an accountant and Partner with KPMG.

This simply means that if you are living, working or travelling abroad but you’re still considered to be a resident of Canada, you’ll have to pay taxes to the federal government. So, when determining whether you are going to have a Canadian tax bill for money earned elsewhere, the first thing to figure out is if you’re still considered a “factual resident” or not.

The Canada Revenue Agency defines someone as a “factual resident” if they maintain “significant residential ties” to Canada. This means you may be temporarily working outside of Canada, vacationing but still have a home in Canada, have a family living in Canada and have a Canadian drivers licence.

To cease residency in Canada, and cease paying taxes to Canada, you have to go about the process of severing residential ties. This means you must no longer have a place to live in Canada, that you have set up a place to live somewhere else, set up financial accounts in a new place, and, if married, have taken your family with you.

Tollstam said that the CRA used to use a 24-month time period to determine non residency, but that has since been eliminated from its guide. She said that basically a minimum of 18 to 24 months away from Canada is now required to be a non-resident.

2.The place where you make your income has first right to tax

But Canada will give you a credit for the tax you have to pay to the country where you earned the income.

For example, let’s say you are working in the U.S. but are still considered a resident of Canada, and you earn $50,000 in the United States. If the U.S. tax on that amount was $7,000 and the Canadian tax on that amount was $10,000, Canada would give you credit on the $7,000 you paid to the U.S.

This means you would have to pay an extra $3,000 to Canada.

“You will pay double tax occasionally, but you generally should not pay double tax,” Tollstam said.

3. It’s still possible to get double taxed

That said, while Canada has tax treaties with different countries that override the domestic law of Canada and laws of the other countries, some non-treaty countries won’t give you full credit for all the taxes paid.

4. You still have to file a return to Canada even if the tax rate is higher in the foreign country

If the tax rate is higher in the foreign country than Canada, you won’t pay anything to Canada on that income.

“But you would still have to file a return and disclose that you had that income, and show [officials] that you paid the tax to the country. [Canada] wants some proof that your paid it,” Tollstam said.

5. Non-residents of Canada are still taxed if they make money in Canada

Sorry, but there’s no exemption from tax just because you’re a non-resident.

“Let’s say you live in the Netherlands but you do come to Canada to do work here for three months,” Tollstam said. “Just because you live in the Netherlands doesn’t mean you’re not taxed on those three months of earnings.”

Once you’re a non-resident, generally speaking you’d cease filing regular returns. But Canadian citizens who are now non-residents may still have periodic income and investments that generate dividends that would also be subject to taxes. This income is generally taxed at a flat rate.

6. The U.S. resident formula

Unlike the factual test in Canada that determines residency, the U.S. taxes non-U.S. citizens based on a very mechanical formula. The calculation is thus: You take all the days you have lived in the United States during the current year, a third of the days you stayed in the U.S. in previous year, and one sixth of the number of days from the year before that. If the sum of those days exceeds 183, you are deemed a U.S. resident.

But it is possible to challenge that. A person can file a “closer connection” statement.

“You basically assert that you have a closer connection to another country and this is why you won’t file a U.S. return,” Tollstam said.

Canada Revenue Agency resources

The Canada Revenue Agency provides a lot of tax information for Canadians living or working abroad on its website:

- To determine whether you are a resident, use the Determination of an Individual’s Residence Status link or fill out a form and send to the government.

- If you have become an emigrant and are no longer a factual resident, check out Emigrants and Income Tax 2011.

- The Federal Foreign Tax Credit link provides you with information on whether you are eligible for such a credit.

- The CRA also lays out tax responsibilities for Canadian residents going down south for extended periods.

- To avoid double taxation, this tax treaties link provides information on treaties with other countries.

Original Posting: http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/taxes/6-must-know-tax-facts-for-canadians-earning-abroad-1.1167892

Why Canadian mutual funds can cause U.S. tax headaches – Repost

Why Canadian mutual funds can cause U.S. tax headaches

Written by: Max Reed

Common Canadian investments can inadvertently cause U.S. tax problems for U.S. citizens in Canada.

Let’s take a really common example that we see frequently. Jack is a U.S. citizen in his 50s who married Jill (a Canadian citizen) many years ago. They have both lived in Canada for a long time. Jack was vaguely aware that he was supposed to be filing U.S. taxes every year. But he didn’t. Then Jack started reading about a recent U.S. law, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) under which his financial institutions would soon be sending his financial information to the IRS by way of the Canada Revenue Agency.

Jack started to comply with his U.S. tax obligations and in the process discovered that his retirement portfolio, which is comprised of Canadian mutual funds and ETFs that are held outside of an RRSP, might cause him problems.

There are strategies that can be used to help someone in Jack’s situation. For instance, Jack can swap his Canadian mutual funds and Canadian-listed ETFs into his RRSP for other investments that may be less problematic. Jack may also be able to gift some of these problematic investments to his wife Jill who is not a U.S. citizen.

Jack’s situation is avoidable with some foresight and planning. Canadian mutual funds and Canadian listed ETFs held outside of an RRSP/RRIF may cause U.S. tax problems. They may (the IRS has not taken a clear position on this and there may be some exceptions to the rule for older funds) be classified as a passive foreign investment company (PFIC) under U.S. tax law. If the investments are classified as PFICs and are held outside of an RRSP/RRIF, they must be reported on a complicated form.

There are punitive tax consequences for owning such an investment. For instance, when the investment is sold, the gain on the investment is subject to tax at up to 35% or 39.6% (depending on the year) and compound interest is charged on the tax owed stretching back to when the investment was purchased. There are strategies available to manage, but not eliminate, this headache but the strategies themselves are quite complicated and likely require the services of a tax professional. The simplest way to avoid this headache is to not own Canadian mutual funds and Canadian listed ETFs outside of an RRSP if you are U.S. citizen.

If Canadian mutual funds and ETFs are owned inside of an RRSP, there is much less of a U.S. tax problem. Recent IRS rule changes have eliminated the annual reporting requirement for Canadian mutual funds and Canadian ETFs held inside of an RRSP. Similarly, the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty (an agreement between Canada and the United States that helps sort out some of the thorny cross-border tax issues) allows U.S. citizens in Canada to defer any tax owed on income accrued inside the RRSP until the income is withdrawn from the RRSP. Many advisors agree that this tax deferral provision likely negates any of the punitive taxes related to the classification of Canadian mutual funds and Canadian ETFs as PFICs as long as the investments are sold before they are taken out of the RRSP. Importantly, the same is not true for other Canadian registered plans such as a TFSA, an RESP, or an RDSP (these plans generally do not work as designed for US tax purposes).

To avoid Jack’s situation, U.S. citizens in Canada should exercise care in making their investment choices. Tax advice should be obtained as necessary.

Original Posting: http://business.financialpost.com/personal-finance/taxes/holiday-series-max-reed-canadian-mutual-funds-cause-u-s-tax-problems

How The U.S. May Tax a Canadian Tax Free Savings Account – Repost

How The U.S. May Tax a Canadian Tax Free Savings Account

Written by: Terry Ritchie

Qualified individuals in Canada can start a Tax Free Savings Account (TFSA) and earn income in a tax-free manner. The TFSA account provides tax benefits for savings where investment income earnings, including capital gains and dividends, are not taxed when withdrawn. However, unlike the Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSP), contributions to a TFSA are not tax deductible for the annual income tax purpose.

The TFSA offers a lucrative and general-purpose savings vehicle for Canadians, who are living in Canada. However, it may not turn out to be as good as it seems for anyone who is subject to tax codes by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This is because, unlike the RRSP, the Internal Revenue Service does not grant tax-deferred status to the Canadian TFSA. Since any income generated in the TSFA is taxed under US law, this taxable status usually takes away any fringe benefits of having a TFSA account for most Canadians residing in the U.S.

The TFSA offers a lucrative and general-purpose savings vehicle for Canadians, who are living in Canada. However, it may not turn out to be as good as it seems for anyone who is subject to tax codes by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This is because, unlike the RRSP, the Internal Revenue Service does not grant tax-deferred status to the Canadian TFSA. Since any income generated in the TSFA is taxed under US law, this taxable status usually takes away any fringe benefits of having a TFSA account for most Canadians residing in the U.S.

Moreover, most Canadians will be required to report the TFSA to the US Department of Treasury on an annual basis, as it is mandatory to submit the Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Account Form TD F 90-22.1. If you are a Canadian, living in the US as a resident, you may have to pay penalties for failing to disclose the TFSA account, which is termed as a foreign bank account.

Again, there are additional concerns regarding whether or not the TFSA will be considered as a foreign trust under the US tax law. There is considerable confusion regarding this, as the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has not revealed their official position on this issue yet. In the circumstance that the IRS decides to consider the TFSA as a foreign trust, the Canadian, who is a U.S. taxpayer, will be termed as an owner of a non-resident trust. As a consequence, the Form 3520-A, titled “Annual Information Return of Foreign Trust With a U.S. Owner,” will be required to be filed within two and half months once the trust’s year ends. Any failure to submit the Form 3520-A with the IRS will be subjected to a penalty greater than $10,000 or 5-percent of the gross value of the trust, which is the total amount left in the TFSA at the end of the tax year.

Then, under the Form 3520, titled “Annual Return To Report Transactions With Foreign Trusts and Receipt of Certain Foreign Gifts,” it may be required to disclose contributions to and withdrawals from the TFSA to the IRS. Any failure to submit this additional form may result in a penalty equal to 35- percent of the contribution or withdrawal amount.

In conclusion, Cardinal Point Wealth Management recommends that U.S. taxpayers, regardless of their current residency status in the U.S. or abroad, consider not contributing to an existing TFSA, withdrawing all remaining TFSA funds, and stopping the use of the account. Following these steps, avoids taxation in both Canada and the United States. For further advice on navigating the complications of cross-border wealth management and taxations, contact us today.

Original Posting: http://cardinalpointwealth.com/how-the-u-s-may-tax-a-canadian-tax-free-savings-account/

Non-Resident RRSP Redemption: Withholding Tax Explained

- June 08, 2015 by Jeanette Boleantu

The Expatriate Group strongly recommends that appropriate tax advice be sought prior to the withdrawal of any RRSP balances. There are two tax consequences that exist for withdrawing registered products before you retire –regardless of your tax residency status.

- The amount you redeem is taxable income: You have to report the amount you take out as part of your worldwide income. At that time, you may have to pay more tax on the money — on top of the withholding tax. It depends on your total income and tax situation.

- You pay a withholding tax: As a non-resident when you redeem RSP there is a 25% withholding tax that is due to CRA. This withholding tax is the NON-RESIDENT TAX LIABILITY on the income received. If a lower amount than 25% is withheld at source or a T3 slip is issued you need to file and pay the difference.

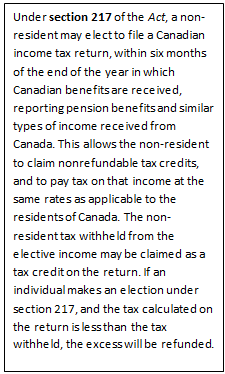

The financial institution will issue an NR4 notifying tax withheld at source in order to avoid filing a tax return as a non-resident. The Section 217 election allows a non-resident to voluntarily file a tax return so that they will have the same tax obligation as if they were a resident of Canada. This is a hassle and we do not recommend doing this. The only time a non-resident should file with CRA is if they received a T3 slip as a result of not changing their residency status on the address maintained with their financial institution.

Before you decide to withdraw your RRSPs, make sure that you consider all of your options. Consult with a

knowledgeable financial professional who can help you figure out the best way to go about making your withdrawals, and who can help you plan for your tax payments. Canadian tax regulations may provide relief from tax and penalties provided that the appropriate tax forms are filed with the CRA. For this reason

knowledgeable financial professional who can help you figure out the best way to go about making your withdrawals, and who can help you plan for your tax payments. Canadian tax regulations may provide relief from tax and penalties provided that the appropriate tax forms are filed with the CRA. For this reasonThe following illustrates the standard amount withheld for Canadian tax residents.

Non-Resident Tax Calculator – Results

Country of residence: Malaysia

Calculation date: 2015-06-05

Income type 1 from Canadian sources: RRSP/RRIF – Lump Sum Payment

Income amount: CAD $ 14,000.00

Tax rate: 25.0 %

Amount payable: CAD $ 3,500.00

Minus tax amount already deducted: CAD $ 0.00

Balance owing: CAD $ 3,500.00