Questions and Answers from an interview with Kerry Gray, partner in the Global Employment Solutions Network Group, Ernst Young Canada LLP

Q: One of the first questions that I would like to ask you about is the tax implication of moving away from Canada — of changing one’s residency status.

A: Under Canadian law, unlike U.S. law, we tax individuals based on residency. The U.S. income tax is based on residency and citizenship

Once a person leaves Canada, he or she is no longer taxable in Canada on non-Canadian income. There are still types of income generated in Canada that they are paying tax on, but in general they are longer subject to worldwide taxation in Canada. What Canada also does is deem individuals to have disposed of certain assets on the date of departure from Canada. Any appreciation that they have on those assets while they were residing in Canada will be subject to a tax. Departure tax is nothing different, it is just income tax that is levied at the time ones ceases to be a resident or departs from Canada.

Q: Do you crystallize everything when you leave Canada?

A: Generally, yes, you are deemed to have sold everything from a Canadian perspective the day that you cease to be a resident.

And all the normal tax rates and exemptions apply?

- Answer. That’s correct. A couple of things that deemed disposition does not apply to includes assets like RRSPs because as a non-resident when you take money out of an RRSP, you still pay Canadian tax. It is not at the old regulated graduated rates and you don’t have to file a return, but Canada would still have the right to tax it. Deemed disposition would also not apply to real property in Canada.

Not until you actually sold the property?

- Answer. Correct, because when you actually sell real estate later on you would still be taxed in Canada

So deemed disposition primarily applies to what we’d refer to as a non-registered investment portfolio?

- Answer. Yes, most commonly to publicly traded stocks in a portfolio.

What else?

- Answer. The deemed disposition rules also apply to personal-use property such as a car or boat, things like coins, paintings and jewellery — if the fair market value of each item or set is greater than $1,000 — foreign real estate and securities, bonds and other commercial paper, unlisted shares, and your interest in a segregated life insurance policy.

Do you have to ante up your departure tax in cold hard cash?

- Answer. For small amounts of departure tax — under $50,000 in taxable capital gains — you don’t actually have to pay. If you sold the asset when you left you have to pay your tax. If you don’t sell it and you have your departure tax apply, you are supposed to post security with the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency.

What kind of security?

- Answer CCRA normally favours letters of credit, bank guarantees, mortgages, negotiable stocks or bonds. When security is posted, the tax will be payable when the property is actually sold and taxpayers aren’t charged interest between the date of departure and the date of disposition.

Now since you’ve had to crystallize your gains, does this affect your adjusted cost base of the investments you may still be holding?

- Answer. No, and that is where if you are moving to the U.S. you need to talk to a tax professional. On the U.S. side of the border, you are not deemed to have bought for the crystallized value on the day that you moved.

Ouch! You mean you are deemed to have bought it the day that you actually acquired the security?

- Answer That’s right.

So you are going to have two sets of capital gains?

- Answer. That’s correct. If someone’s moves into Canada, Canada deems you to buy things the day that you move in and sell things the day that you move out. The U.S. does not do that. Canada says, “Okay, we have some transitional rules because there is an exposure to double tax, in that the U.S. doesn’t say that your basis is the fair value the day that you move into U.S.” So there are some transitional provisions in place in Canada allow you to claim a foreign tax credit against the Canadian tax so you are not double taxed.

So since the U.S. doesn’t recognize the basis bump when you sell, if you have to pay U.S. tax, Canada will give you a credit for the amount of U.S. tax that you owe on the gain up to the point in time that you left Canada?

- Answer Correct. So let’s say your deemed disposition is $100,000 when you left Canada, but it grows another $50,000. You can’t claim U.S. tax on a $150,000 against your Canadian tax on a $100,000. You can only pick up the U.S. tax on the $100,000.

So are there circumstances where it just makes sense to sell the investment to avoid all this complicated stuff?

- Answer. Depending on what the asset is and what you think is going to happen with the asset and what state you are moving to you might want to actually sell the asset and rebuy it instead of just having the deemed disposition. This is where it the planning becomes interesting. The individual states in the U.S. have various tax rules. Some have no personal tax, some have personal tax, some don’t tax capital gains. So you have to understand where you are going, and know the beast you are looking at.

So it is not enough to say that I am moving to the U.S., you have to say I am moving to such-and-such a state. I don’t think that Canadians have that appreciation because while we have different tax rates provincially, barring Quebec, most of our tax rules are homogeneous. I don’t think Canadians have an appreciation for the independence that U.S. states have.

Anything else?

- Answer. Can we go back for a moment on the real estate — to your Canadian home?

- Generally you never pay tax on the gain on your principal residence in Canada. And that holds true in general so long as you sell your home it the year that you leave or by the end of the calendar year following the year of departure. In the U.S., however, there is a special provision on the Canada/U.S. income tax treaty that does give you a basis adjustment up on that home. So even if you close on your home sale after you arrived in the U.S., generally you won’t pay U.S. tax as long as you sell it for an amount of no greater than the value at the point of time that you left Canada.

- So it is a special provision under the treaty that allows you to revalue your home. But once again, you have to check and see if the individual state [to which you’re moving] follows the treaty. It is not a slam-dunk that individual states do that.

So you can’t assume anything?

- Answer. That’s right. You have to check out everything.

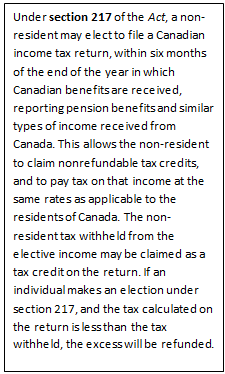

knowledgeable financial professional who can help you figure out the best way to go about making your withdrawals, and who can help you plan for your tax payments. Canadian tax regulations may provide relief from tax and penalties provided that the appropriate tax forms are filed with the CRA. For this reason

knowledgeable financial professional who can help you figure out the best way to go about making your withdrawals, and who can help you plan for your tax payments. Canadian tax regulations may provide relief from tax and penalties provided that the appropriate tax forms are filed with the CRA. For this reason